It was 1972. A wedding in Long Beach requested our presence, a friend in our tight-knit group to join with his true love in holy matrimony. So we embarked on a road trip to the West Coast, that fabled land of golden sunsets and salty air. A 1930s wedding theme had been announced, so for weeks prior to the trip, I had worked feverishly to sew a gangsta-style three-piece suit in pink gabardine for my husband Frank and a long-waisted light yellow dotted Swiss dress for me. Our friend Virginia, who provided her bright yellow VW bug convertible for the journey, got busy sewing her own pink vintage-style dress for the occasion.

We had plenty of fun planning the trip, gathering wide brimmed hats, Frank’s fedora, the gloves, the hand-held fans. Freshly inspired by Hunter S. Thompson’s Fear and Loathing book, we gathered the requisite pharmacy, tame in comparison to his. The itinerary grew with each passing day. On the way out there, we’d see the sights traveling in tandem with Jeff, Robert, and Franz in Robert’s shiny blue Karmann Ghia convertible.

The day arrived. We loaded up at Jeff’s house and then headed west, tops down and hair flying in the wind. In those days, Interstate 40 had not been completed. Especially in Oklahoma we found ourselves detoured through small dusty towns on the well-worn two lanes of old Route 66.

Long before Oklahoma City, we put up the ragtop to stop the torrent of wind tearing around us. Somewhere before that, my beautiful paisley turquoise silk headscarf disappeared into the landscape. Late that night, past Tucumcari and facing into a storm front that lit up the sky with magnificent lightning, the front hood flew open and the garment bag with our wedding clothes blew out. Frank steered to the shoulder, latched the hood, and backed up until we found the bag lying unharmed in the median.

More hours passed. We made the last curve around a dark mountain and Albuquerque spread out below like a bowl of lights. The garment bag fiasco separated us from the other car but we couldn’t go another mile. A cheap motel room felt like the Hilton.

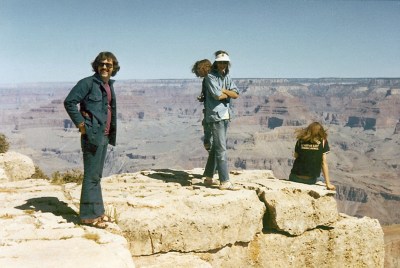

The next morning, a quick drive through the Painted Desert and Petrified Forest renewed our wonder in the natural world. We made our rendezvous with the other car late the second night at the Grand Canyon. I spent a miserable night freezing in a too-short sleeping bag on rocky ground, probably no worse off than the rest of us. The next morning some of us dropped acid for a walkabout along the south rim. The Grand Canyon is mind-blowing on its own. With LSD, it became a second-by-second discovery of bizarre vegetation, rocks of every epoch, and the mystery of distance, time, and existence. Then we were on our way again.

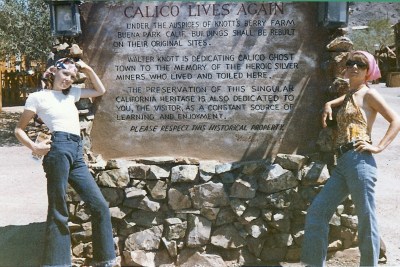

The wedding was complicated—people we didn’t know, extended family, a church and reception. Before and after, we wandered through L.A.’s farmers market, Hollywood, Venice Beach and other places along the seafront. With the happy couple off on their honeymoon and the Karmann Ghia headed home, we set off to the north. From Santa Barbara we followed Highway 1, that hair-raising winding roadway that clings to the cliffs along Big Sur. I don’t do well with heights. My knees start shaking at the third rung of a ladder. I alternated between sickening glances down at the waves smashing onto rocks and hiding my face in my hands.

Exhausted, we gave up just south of Monterey and parked at the side of the road for the night. Thanks to Frank’s heroic decision to sleep outside, Virginia took the front and I had the back. Neither of us could lie down since there was the matter of bucket seats and gearshift in the front and an ice chest and assorted miscellany in the back. As it turned out, we both had it better than Frank who woke us in the frigid pre-dawn fog desperate to get warm.

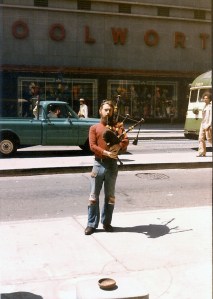

Disheveled and bone tired, we toured San Francisco, a drive-by effort to see the Presidio, Golden Gate bridge, and Fisherman’s Wharf. We walked through downtown, gawking up at tall buildings, dodging cable cars, and musing over oddities like the man playing bagpipes across the street from Woolworths. We wandered around the fabulous Palace of Fine Arts, a preserved portion of the original 1915 exhibit for the Panama-Pacific Exposition.

At this point we had sixty-five dollars to get us back to Northwest Arkansas. There would be no more cheap motels or souvenirs and precious little food. Even with gas at 35 cents per gallon, we hardly had enough to get us home. Fortunately, Virginia had a Gulf credit card. We drove all night, white lines blurring down the pavement as we crossed the gray-white moonscape of Nevada. We hit Salt Lake City sometime the next morning and found a truck stop with showers and a buffet, all of which we could charge on her card.

After a brief gander at Mormon temples, we stuffed ourselves back into the increasingly crowded VW and dove into the Rockies. Up and down we drove, steep inclines, terrifying drop-offs, and legitimate worries about the VW’s clutch and brakes. Frank’s old friend John and his wife lived on the other side of all those snow-capped peaks at a little mining town called Leadville. He welcomed us with cocktails, grilled steaks, and a loft sleeping area in his mountainside chalet.

Oh the joy.

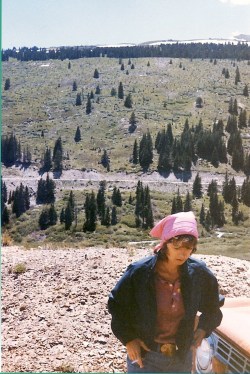

The next day, John took us sightseeing. Included in his agenda was an abandoned silver mine he’d discovered. What is commonly known as a road disappeared before we left the valley floor and soon we found ourselves clinging to the mountainside on a trail of sliding scree hardly wide enough for the Bronco’s wheel base. John was famous for his wild and crazy antics as a Kappa Sig in college, and he’d forged into Vietnam with the bravado only a lieutenant on point can respect. His patrol had walked into a land mine which nearly cost him his life, so when we neared the silver mine and the vehicle canted to a forty-five degree angle and he said ‘oh shit,’ it was truly an ‘oh shit’ moment.

We gingerly crawled out of the vehicle on the high side and while Virginia and I watched, John and Frank began digging out from under the wheels in an attempt to level the vehicle. We lost track of time out there in the thin air. The view was breathtaking. Unfortunately, my breath had already been taken by the vertical drop-off to the distant valley below where towering evergreens looked like matchsticks. I was sure we were all going to die.

Over an hour later, John deemed the vehicle level enough that he dared climb inside to drive back up to level ground. With his success, I reluctantly re-entered the vehicle for the remaining terrifying jaunt to the mine. Scavengers had been here many times, but we wandered around thinking of the old timers who came up here with a mule and a pick to seek their fortunes.

Glittering chunks of ore scattered over the rocky ground. The old log structure wasn’t safe to walk in, but we nosed around in the scattered remains where I found a little Carter’s Ink bottle buried bottom up in the dirt. It had turned blue-green in the decades since its contents had been used to pen letters home or tally the proceeds of a day’s hard work. I tucked it in my pocket and braced for the slip-slide trek back down.

Glittering chunks of ore scattered over the rocky ground. The old log structure wasn’t safe to walk in, but we nosed around in the scattered remains where I found a little Carter’s Ink bottle buried bottom up in the dirt. It had turned blue-green in the decades since its contents had been used to pen letters home or tally the proceeds of a day’s hard work. I tucked it in my pocket and braced for the slip-slide trek back down.

From Leadville we hurried south to hit our planned stops at Garden of the Gods and Royal Gorge before turning east for the last leg of the journey. If you’ve never crossed Kansas, be warned—it’s the original never-ending story. You drive and drive and you’re still in the same place. We had cleverly planned what seemed the shortest route but which turned out to be a maze of two lane roads to nowhere. It got dark, the gas gauge sat on empty, and we were in the middle of corn fields with lightning forking across the sky.

Somehow we found our way to a tiny town and waited until the local gas station opened. Later that afternoon, crammed into the back seat with relics of our journey towering in the seat beside me, claustrophobia got me by the throat and I had to get out of the car. We stopped while I walked in the gravel along the side of the road and said I could not get back in that car. Finally Frank convinced me to try the front seat and he squeezed into the back for the rest of the way home.

So many memories, so many emotions. Frank is no longer among the living, nor is Robert. The rest of us keep growing older. But when I think about that summer vacation, I’m lost in the past, my hair flying in the wind, our laughter ringing up the hillsides. I hold that ink bottle in my hand and I’m back in the hot sun smelling pine in cool air and breaking my fingernails as I dig it out of that hard packed ground.

We did things, went places, had adventures. We experienced profound wonder that never left us. We grew. I see now—that’s what vacations are for.