Laws against drug use do not stop drug use or abuse. Instead, such laws and their enforcement exacerbate conditions in individuals which have led to their substance abuse. Current drug policy feeds a system of violence by funneling drug traffic to underground markets which in turn finance gangs and cartels. This violence escalates as community law enforcement shifts toward militarized weaponry and strategies, which leads to violations of individual, constitutionally-guaranteed rights. Meanwhile, taxpayers fund ever increasing costs for failed policies.

The Money $$

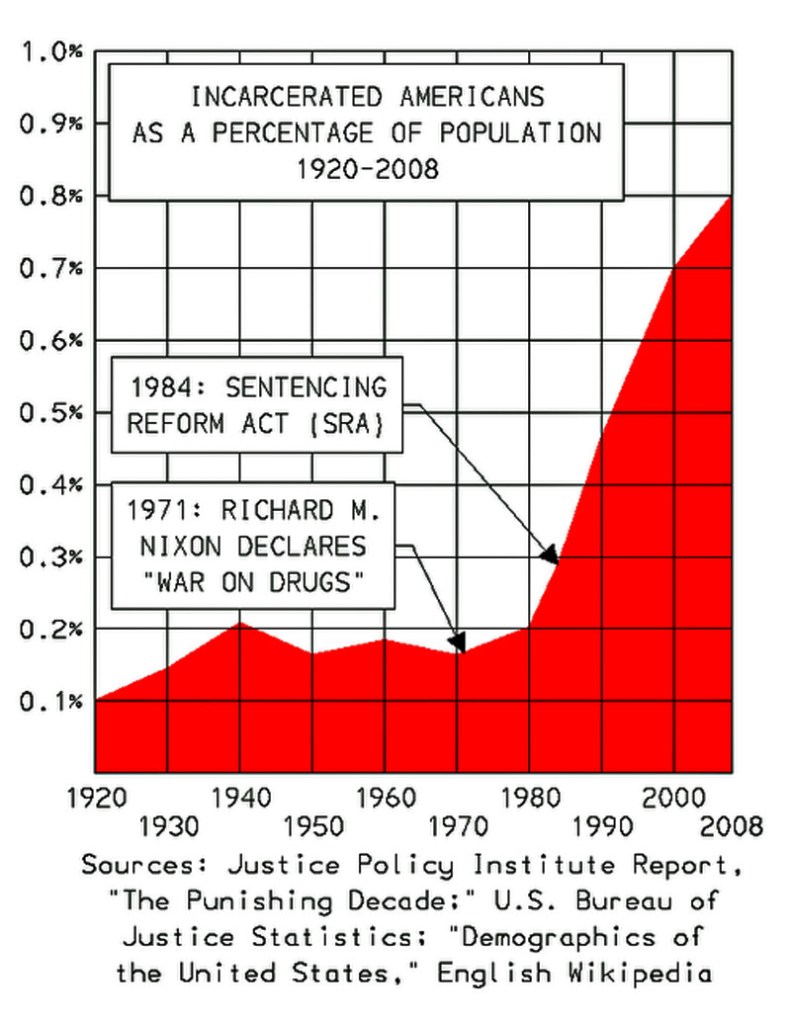

Incarcerating drug offenders costs U.S. taxpayers over $10 billion annually for over 485,000 prisoners. The federal government spends approximately one million dollars per day just on drug-related incarcerations, with state governments spending billions more. The average annual cost to incarcerate a single person is roughly $40,000 to over $65,000, far exceeding the cost of treatment.[1]

- Imprisonment: $10 billion

Beyond incarceration, the total cost for police, prosecution, and adjudication of drug law violations are estimated at over $47 billion per year. Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) budget for 2021 (last available year) was $3.28 billion.

- Enforcement: $47 billion.

When including the societal costs of substance abuse (health care, criminal justice, lost productivity), the total impact is estimated at over $500 billion annually for substance abusers. Then there’s the cost of social services for families of persons convicted for drug crimes. An average of nearly $4,200 annually is paid by families to support their incarcerated loved ones, with a cumulative financial burden on families estimated at approximately $350 billion per year nationwide. Federal prison populations average 42.9% drug prisoners, costing tax payers $150 billion in social services for their dependents, while state prisons contain an average of 20% for drug crimes adding another $70 billion for social services, a total of $220 billion.[2][3]

- Society: $720 billion.

The total societal cost for individuals with substance abuse problems, including lost productivity and health consequences, is much higher, with estimates exceeding $820 billion annually. For illegal drugs, the cost is estimated at $193 billion.

- Personal: $193 billion[4]

The United States military spends roughly $1 billion annually directly on drug interdiction and counter-drug activities, with over $8 billion in surplus equipment transferred to law enforcement agencies since 1990. This spending involves the Department of Defense (DoD) supporting federal, state, and local agencies through intelligence, surveillance, and equipment transfers, particularly through the 1033 program.[5]

- Military: $9 billion

Total estimated dollar cost of the U.S. drug war: $979 billion ANNUALLY.

The Human Cost

Roughly 75% of illegal drug users are self-medicating.[6] Research has shown that people with conditions like depression, anxiety disorders, bipolar disorder, PTSD, and ADHD may use illegal drugs to temporarily alleviate symptoms. For example, a person struggling with alcoholism through most of the fifty years of his life seeks therapy and discovers that he was bi-polar. Once appropriately medicated for bi-polar disorder, he no longer cared to drink. Many patients misusing drugs and alcohol have chronic pain and use these substances (such as marijuana and heroin, which have pain-relieving properties) to cope. Finally, in the absence of emotional support, individuals may use drugs to deal with increased stress, trauma, or a recent loss.

In a nation eager to spend billions of dollars to punish intoxication, far less energy and money is expended to provide physical and mental health care for persons in need. Illegal street drugs are less expensive than medical care. Even subsidized medical care often fails to fully address mental health or nutritional needs. For a chronically depressed person, for example, methamphetamine can elevate that person’s mood. Opiates can also seem the perfect answer, i.e. escape from reality.

Enforcement of prohibition laws further harms a person using illegal drugs. Humiliation, disenfranchisement, and poverty are collateral damage intentionally inflicted by arrest and prosecution. An arrest or conviction record can lead to eviction or denial of housing, particularly in public housing, with formerly incarcerated people being ten times more likely to experience homelessness. Interactions with the legal system can trigger child welfare investigations, potentially leading to family separation and foster care placement, adding to generational damage. Consequences can include the loss of voting rights, firearm privileges, and driver’s license suspension. Individuals may lose access to student loans, public benefits (like TANF or SNAP), and face significant financial burdens. These deleterious effects of prohibition laws only exacerbate an individual’s underlying problems.

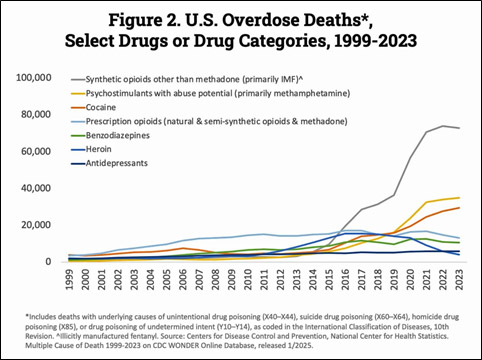

There were approximately 105,000 to 108,000 annual drug overdose deaths reported in 2022 and 2023, with provisional data for 2024 indicating a significant decrease to around 80,000–81,700 deaths. The vast majority of these deaths involve illicit drugs, specifically synthetic opioids like illegally-made fentanyl, the primary driver of the overdose crisis in the United States, responsible for approximately 72,000 to 73,000 deaths annually as of 2023. These synthetic opioids account for nearly 70% of all illegal drug-related deaths.

Between 2001 and 2018, deaths from drug and alcohol intoxications in prisons and jails rose 600% and 400%, respectively. Factors in these surprising numbers include limited access to evidence-based treatment, such as Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT) (e.g., methadone, buprenorphine), and high-turnover, high-stress environments. Additionally, researchers suggest that the true number of intoxication-related deaths is likely higher, as many are often miscoded on death certificates as “illness” or “unknown” causes, particularly when they occur shortly after booking. Treatment or medications for substance use disorder are rarely available behind bars.[7]

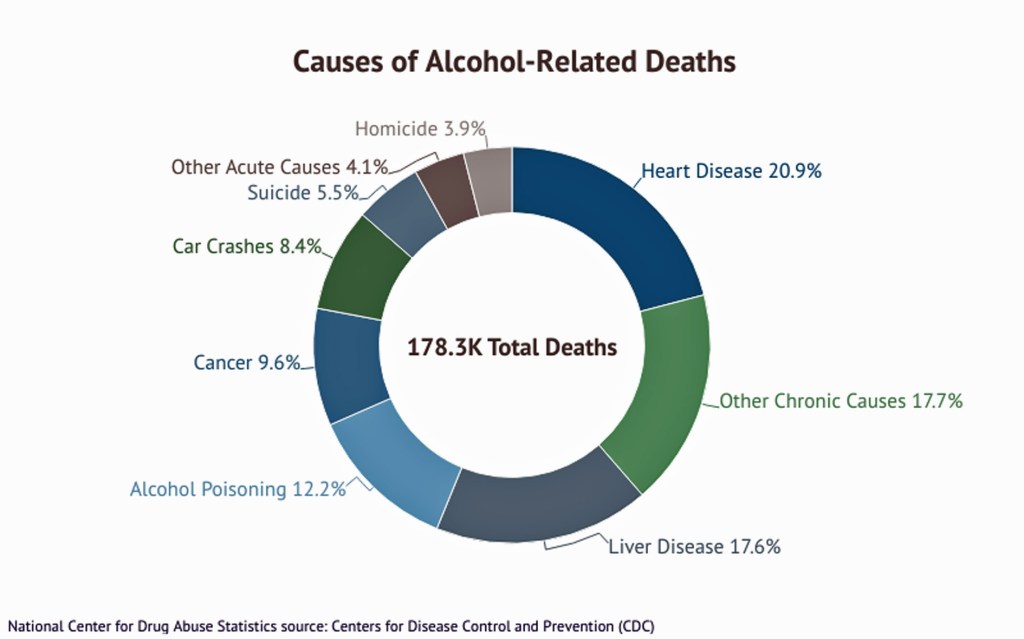

What makes the news are deaths from fentanyl, over 80,000 annually as noted above. But compared to drug deaths, deaths from legal alcohol use are estimated at 178,000 annually. Additionally, another 13,000 deaths (average) per year result from drunk driving. Excessive alcohol use remains a leading preventable cause of death, with estimates frequently exceeding 100,000 annual deaths attributable to chronic health conditions and acute events like accidents.[8]

Death from illegal drugs:

- 2024 (Provisional): Approximately 79,384 drug overdose deaths were reported, representing a substantial, nearly 24% decrease from 2023.

- 2023: Approximately 105,007 people died from drug overdoses, which was a slight decrease (about 3%) from the 107,941 deaths reported in 2022.

- 2022: A total of 107,941 drug overdose deaths occurred.

- 2021: A total of 106,699 drug overdose deaths

In comparison, deaths due to excessive alcohol use increased from 30,722 in 2014 to 54,258 in 2020-21 to 46,796 in 2024. These are direct results while alcohol-related causes totaled 178,000 deaths “in an average year.”[9] Polling shows that 54% of adults say that someone in their household has struggled with an alcohol use disorder.[10]

As we should have learned from efforts to eliminate alcohol use/abuse with the 1920 passage of the Volstead Act (repealed in 1933), prohibition laws open a vast underground market where criminals earn huge profits by supplying prohibited substances to the public. While there is no single definitive figure for the total size of the underground alcohol market between 1920 and 1933, the federal government lost an estimated $11 billion in tax revenue during Prohibition and spent another estimated $300 million in enforcement. Meanwhile, organized crime syndicates flourished, with major figures like Al Capone generating up to $100 million annually. Deaths attributed to alcohol poisoning during the thirteen years of prohibition are estimated at 50,000, i.e. slightly less than 4,000 per year.[11] This total is separate from other alcohol-related deaths including drunk driving and alcohol-related diseases such as cirrhosis of the liver.

Worse than the dollar cost for the current prohibition laws on certain drugs, however, is the human cost and the cost to our democracy.

Prohibition was—and is—a powerful political tool heralded by countless public office hopefuls who don’t hesitate to proclaim their support for prohibition laws. Notably, President Donald Trump has used drug trafficking to justify the outright murder of (so far) over 130 individuals by claiming they were carrying drugs in their boats—no judge, no jury.[12] Keep in mind that over 100,000 people die each year from prescribed drugs. Legal drugs. These include psychostimulants, cocaine, prescription opioids, benzodiazepines, heroin, antidepressants.

Data shows us that 27.9 million people, 9.7% of the population, will suffer an alcohol use disorder, while 28.2 million (9.8%) will suffer a drug use disorder. Equally noteworthy is that 21.2 million people had both a mental health disorder and a substance use disorder.[13] Other evidence is found to support the idea that at least half of persons with a substance abuse problem are self-medicating an underlying problem. Contributing factors include early use (before age 15 compared to those who wait until age 21 or later) and/or a family history of problem drinking. Altogether, nearly 20%–one in five people—face substance abuse problems.

The cost to our democracy is not just the extra-judicial murder of people in boats. It is the ridiculous idea that the government has the right and capability to monitor individual lives. To this end, government has armed community police departments with military-grade weapons and the development of SWAT teams in order to carry out the ‘war’ on our citizens. Yes, this is a response to wealthy street gangs protecting their turf against competing gangs as well as against law enforcement, but prohibition policies created this war that can never be won. People will continue to recreate and self-medicate. Police will continue to try to enforce the laws, failed as they are. Such laws open the way to selective enforcement, wherein persons of color or low income become easy targets. Black people are significantly more likely to be arrested for drug violations, with studies showing they are 3.6 times more likely than white people to be arrested for marijuana possession. Black and Latino people make up the majority of those in state and federal prisons for drug offenses. The imprisonment rate for Black adults for drug charges is nearly six times that of white adults. Almost never does law enforcement act against the wealthy or other ‘elites’ who most certainly can access effective legal advice before ever entering a jail cell.

These shameful outcomes in a so-called free society are due to the fact that drug laws are fundamentally unenforceable. Government cannot surveil private activity in the homes of American citizens, so traffic stops for spurious reasons lead to police sniffing the air rolling out of the car window to justify acceleration of their ‘investigation.’

This ouroboros of ill-considered public policy not only destroys our communities, it infects the entire nation with violence and lost opportunities.

Cost of Appropriate Care for Persons with Substance Abuse Disorder

Experts emphasize that substance abuse is often both a cause and a consequence of homelessness. While addiction can contribute to housing loss, many individuals also experience substance use as a form of “self-medication” to cope with the trauma and physical pain of living without stable housing, as previously discussed.

Walk-in, free community health clinics that focus on addiction treatment should include excellent nutrition, mental health diagnosis and treatment, and healing exercise (T’ai chi, mindful meditation, low impact exercises, walking, swimming). Such clinics must be established in every community where homeless populations are found and, subsequently, in every community of 25,000 or fewer or equivalent parts of larger communities. Each person must be linked with a counselor who advises not only on treatment options, but also on what social services are available and recommended, to include physical (including dental) and mental health care, educational options, job training programs, counseling on matters of family, personal relationships, and living conditions. Referral to housing with follow-up oversight requires that housing be available.

Housing for unsheltered persons is an important element in addressing addiction and mental health issues. Permanent Supportive Housing (PSH) is the gold standard for individuals experiencing chronic homelessness who have diagnosed disabilities. It combines long-term, stable housing with intensive, voluntary supportive services (such as mental health care, addiction treatment, and case management) to ensure long-term success. Cost: $12,000–$20,000 range, with some specialized cases involving higher service needs costing more. Rapid Re-Housing (RRH), often in the form of tiny home villages, is best suited for those experiencing non-chronic homelessness. This model focuses on getting individuals into their own apartments as quickly as possible. It provides short-term financial assistance (rent/utilities) and time-limited support services to help people stabilize and gain independence. RRH is lower-cost, short-to-medium-term assistance, estimated at roughly $8,500 annually.

Many experts argue that the high cost of homelessness—driven by public spending on emergency rooms, jails, hospitals, and crisis services—often exceeds the cost of providing stable, permanent housing.

National Alliance to End Homelessness:

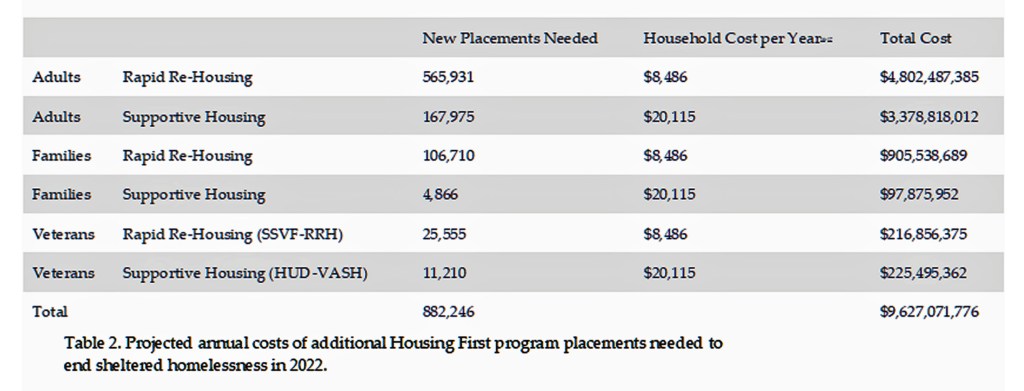

We calculated the additional Housing First placements needed to provide assistance for every household who experienced sheltered homelessness in 2022. Table 2 applies financial cost estimates (in 2022 dollars) to this expansion in placements. At an annual cost of $8,486 and $20,115 per adult household for each placement in Rapid Re-Housing and supportive housing, respectively, it would cost an additional $8.2 billion to rehouse all adult households who stayed in shelter in 2022.

The comparatively smaller number of families experiencing homelessness, almost all of whom are temporarily homeless, would mean that all sheltered homeless families could be rehoused using Rapid Re-Housing at an additional annual cost of $1 billion. The highly successful veterans Housing First placements can be expanded to cover all sheltered homeless veterans at an additional annual cost of $442 million. At an estimated total additional cost of $9.6 billion, all households that used shelter in 2022 could have been provided with a Housing First program.

Between 2001 and 2018, deaths from drug and alcohol intoxications in prisons and jails rose 600% and 400%, respectively. Treatment or medications for substance use disorder are rarely available behind bars.[14]

Estimated number of homeless persons in the United States (2024) is 772,000. For this number, high end estimated cost for PSH would total $15.4 billion.

Subtracted from the savings found in ending the drug war, providing housing for the homeless would leave $963.6 billion for other uses.

Lost Potential Income

The global illegal drug industry is estimated to be worth between $426 billion and $652 billion per year. The United States illegal drug industry is estimated to be worth between $200 billion and $750 billion per year. If you believe the people profiting from this income flow will hesitate to spend some of their ill-gotten wealth to lobby legislators at any hint of drug policy reform, I have a bridge to sell you.

If currently illegal drugs were legalized in the United States, regulated like alcohol for purity and dosage strength, and taxed, the income from those taxes would range between $7.5 billion and $225 billion per year. This 3% approximation is based on the rate used on alcohol in Arkansas. Alcohol tax differs from state to state, in addition to federal tax per ounce of pure alcoholic content. For spirits, wine, and beer, the federal rate is 21 cents, 6 cents, and 9 cents, respectively, leaving no easy method of comparing alcohol tax rates to potential tax on currently illegal drugs. No doubt a modest tax rate on what is currently sold on the black market would be substantial. Potential tax income from legalized drug tax: $7.5 to $225 billion.

Also profiting the nation would be new income for farmers, processors, and retailers providing drugs to the public. For comparison, consider the Arkansas medical marijuana market. Since its 2019 launch, the Arkansas medical marijuana industry has exceeded $1.1 billion in total sales. In February and March 2024 combined, the state’s 38 dispensaries sold nearly $45 million in products. As of March 2, 2026, the average annual pay for a Cannabis Grower in Arkansas is $51,905 ($24.95/hour), with most salaries ranging from $31,100 to $66,500. Top earners (90th percentile) in the Arkansas cannabis cultivation sector can make up to $81,841 annually. Broader roles within the Arkansas cannabis industry average around $118,867 a year ($57.15/hour). Of key note, Arkansas has collected over $127 million in state tax revenue from medical marijuana in the last five years.

Imagine these numbers amplified if production and sales weren’t limited to people certified as medical use! Instead, current policies are supporting various actors in this international underground drug trade, including:

- Transnational Criminal Organizations (Cartels): These “international logistics companies” manage the large-scale trafficking and distribution. Leaders (“kingpins”) can accumulate immense personal fortunes, often running into billions of dollars, though the majority of revenue is distributed among lower-level participants in destination countries.

- Wholesalers and Distributors: Individuals in destination countries like the US and the UK who break down large shipments and distribute them to local dealers capture an estimated 70% to 80% of the total revenue, primarily due to the high retail price and significant risks involved at this stage of the supply chain.

- Street-level Dealers: While often making modest incomes (sometimes compared to minimum wage, though still a living wage for many), these individuals are numerous and collectively account for a large portion of the market’s revenue. Their earnings are often used for everyday living expenses.

- Farmers and Producers: At the very beginning of the supply chain, farmers in producer countries (e.g., Afghanistan for poppy, Colombia for coca) earn very little compared to the final street value of the drugs.

- Corrupt Officials: Bribes and payoffs supplement the incomes of government officials, police, and border control agents at various levels, enabling the flow of drugs and money.

- Professionals involved in Money Laundering: Individuals such as lawyers and accountants are involved in creating shell companies, using offshore accounts, and running cash-intensive businesses (like bars, salons, or construction companies) to disguise illicit funds as legitimate income.

- Legitimate Businesses: Drug money is often laundered by investing it in the legitimate economy, including the stock market, real estate, and various small businesses, which in turn profits from these cash infusions.

- For example, a DEA memo, part of a recent (early 2026) release of Justice Department files, shows that the agency opened an investigation into Jeffrey Epstein and others in December 2010. The investigation was still pending as of 2015, the date of the memo. The document specifically noted that Epstein was suspected of transferring more than $5.6 million for the purpose of acquiring narcotics.

Ultimately, illegal profits sustain the operations of the entire criminal network and fund related illicit activities such as human trafficking and arms trafficking.

Farmers would be one of the primary beneficiaries of legalized drugs, capable of producing not only crops of marijuana, but also opium poppies and coca bush. The two latter agricultural products are well established outside the continental U.S., as are harvesting and processing methods. Populations which have traditionally produced opium are primarily Afghanistan and parts of the North-West Frontier Province (now Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan). Coca production and processing are traditionally in Peru, Bolivia, Colombia, and Ecuador. These areas would greatly benefit from legalizing their farming of these substances.

Clearly, ending the U.S. drug war would create tremendous benefits around the world.

The Drug War’s Role in Illegal Immigration

In particular, legalized drugs would remove the U.S. boot from the necks of Central and South American nations whose drug cartels currently exercise a combination of extreme violence, territorial control, corruption, and diversification into other criminal and legitimate economic activities in their home nations. Drug cartels exert a profound, direct, and increasingly violent influence on immigration into the United States by controlling, taxing, and facilitating the movement of people across the U.S.-Mexico border. They have transformed migrant smuggling into a multi-billion dollar business that often works in tandem with drug trafficking, turning the border into a “pay-to-pass” system.

But that is only part of the drug war benefit to cartels in the immigration arena. Violence, including that stemming from drug trafficking, gang activity (maras), and extortion, is a primary driver of emigration from Central America, with studies suggesting it acts as a, or the, main catalyst for 39% to over 60% of migrants, particularly from the “Northern Triangle” (El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala). The violence associated with the drug trade damages local economies, reduces investment, and destroys jobs. Research indicates that this “economic channel” is the dominant force behind migration, as people flee not just the immediate threat of violence, but the loss of livelihood. Gangs frequently target youth for forced recruitment, leading many families to send their children to the U.S. for safety, resulting in surges of unaccompanied minors.

The immigration problem for the U.S. is not limited to Central America. Even further south from our borders are people desperate to leave South America. The majority of South American immigrants to the southern border of the United States are from Colombia, Venezuela, Brazil, Ecuador, and Peru.

As of early 2026, the political-economic situation regarding the drug war in Venezuela is defined by a deeply entrenched, state-involved narco-trafficking infrastructure that functions amid a severe economic, humanitarian crisis, and intense pressure from the United States. The government is largely seen as a “gangster state” where, under the Maduro regime, the military and security apparatus became reliant on illicit revenue streams to maintain power, particularly through the “Cartel of the Suns”. Roughly 49% to over 72% of Venezuelan migrants to the U.S. have cited insecurity and violence as a reason for leaving their country.

As of early 2025, over 400,000 Ecuadorians had left the country since 2021, with a significant and growing percentage driven by drug war violence and, in some cases, forced recruitment. The political and economic situation regarding the drug war in Ecuador is characterized by a “new phase” of intense, US-backed military operations against “narco-terrorist” gangs, which have largely taken over criminal control of the country’s Pacific ports. Despite President Daniel Noboa’s “iron fist” policies—declaring an internal armed conflict and deploying the military—homicides reached record-highs in 2025, with over 9,000 violent deaths, making it one of the most violent nations in the world.

The political and economic situation regarding the drug war in Colombia in early 2026 is characterized by heightened tensions with the United States, record-high cocaine production, and a contentious shift in strategy under President Gustavo Petro. Cocaine trafficking is a massive, parallel economy in Colombia, generating an estimated $15.3 billion annually, equivalent to roughly 4.2% of the country’s GDP. Petro has moved away from forced eradication toward voluntary substitution and “total peace” negotiations with armed groups, a policy that has struggled to show results and has antagonized the Trump administration.

In Brazil, the highest rates of homicide, often linked to drug trafficking disputes, are concentrated in the North and Northeast regions, prompting migration from these areas. Brazil struggles with high rates of homicide (roughly 23.8 per 100,000 residents), gang violence, and robbery, largely driven by the illegal drug trade.

In Peru’s rural, coca-growing regions like the VRAEM (Valley of the Apurímac, Ene, and Mantaro Rivers), violence, extortion, and illegal mining have forced many to leave. Drug traffickers have increased violence against indigenous communities, causing displacement. The reduction of USAID funding, particularly under the Trump administration, has created uncertainty regarding the continuation of alternative development programs that were designed to encourage farmers to switch from coca to legal crops.

Overall, immigration enforcement and border security costs have reached record highs in the U.S., with proposed and approved funding for FY2025–2026 exceeding $100 billion over four years, including a roughly $10 billion annual budget for U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and nearly $20 billion for U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) in 2024. Recent legislation has significantly boosted these figures, allocating $45 billion for detention, $30 billion for removals, and $46 billion for border walls, creating a massive “deportation-industrial complex.”

Obviously, ending the drug war would destroy the cartels, thereby allowing for a return to normalcy in these Central and South American nations. Granted, this won’t occur overnight. The damage has occurred over decades. Still, if such an improvement came to pass, we could estimate at the very least a 50% reduction in this budget, from $100 billion to $50 billion, and probably significantly more.

Dispensing Drugs in a No-Prohibition Nation

Almost 300 million people are estimated to consume illicit drugs regularly, with the three most popular being cannabis (228 million users), opioids (60 million) and cocaine (23 million). But that is a drop in the bucket to the actual drug consumption. Nearly 260 million Americans use over-the-counter (OTC) medications, purchasing them an average of 26 times per year. In 2024, OTC medication sales in the U.S. were estimated at $44.3 billion. Studies show that 81% of U.S. adults used at least one OTC medication, prescription medication, or dietary supplement in the past week. Further, approximately 6.3 billion prescriptions were filled in the U.S. in 2020 alone. Nearly two-thirds of U.S. adults (about 64.8%) report taking at least one prescription medication annually, treating conditions such as Type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol.

The mean cost of developing a new drug from 2000 to 2018 was $172.7 million (2018 dollars) but increased to $515.8 million when cost of failures was included and to $879.3 million when both drug development failure and capital costs were included. Clearly pharmaceutical companies are betting on a return, with profits. According to the healthcare intelligence company IQVIA, the U.S. alone accounted for nearly half of all worldwide prescription drug sales in 2024, generating almost $800 billion in revenue, within a global pharma market estimated at $1.7 trillion. Pharmaceutical companies spend over $10 billion annually on direct-to-consumer (DTC) advertising in the U.S., with the top 10 drugs accounting for over one-third of that total. TV ads represent about half of this, totaling over $5 billion. Total marketing and sales spending for some major companies, such as AbbVie and Johnson & Johnson, frequently exceeds their research and development (R&D) budgets.[15]

Face it. Drugs are everywhere. Large signs declare “DRUGSTORE.” Television offers drug advertisements up to 16 hours of drug ads per year, with some studies suggesting even higher exposure of over 30 hours, exceeding the average time spent with a primary care physician. The pharmaceutical industry spends billions on direct-to-consumer (DTC) advertising, with $6.58 billion spent in 2020 alone. The U.S. is one of only two countries—along with New Zealand—that allows direct-to-consumer drug advertising on TV. As the population ages and chronic disease rates rise, pharmaceutical companies have responded by increasing their ad spend to promote new and patented drugs directly to consumers.

According to the FDA’s Office of Prescription Drug Promotion, these are the most common issues found in today’s drug commercials: Omitting or downplaying of risk; Overstating the drug’s benefits; Failing to present a “fair balance” of risk and benefit information; Omitting material facts about the drug; Making claims that are not appropriately supported; Misrepresenting data from studies; Making misleading drug comparisons; and Misbranding an investigational drug.[16] Not mentioned is the unstated theme that every human problem can be solved with medication. Ads show the medicated person suddenly surrounded by happy dancing people reveling in sunny vistas of idyllic surroundings.

Direct-to-consumer advertising has contributed to a rise in overall prescription drug use among Americans, from 39% (1988-1994) to nearly 50% (2017-2020), fostering a culture that seeks pharmaceutical solutions for various conditions. The most direct parallel occurred in the late 1990s, when pharmaceutical companies aggressively marketed opioids (like OxyContin). The deluge of marketing fueled over-prescription, leading to widespread addiction, and as legal restrictions increased, many users shifted to cheaper illegal alternatives like heroin and fentanyl, according to experts.[17]

Drugs, like alcohol, are also useful for recreation, a way to quickly switch one’s mood and energy from the caffeine-fueled drive to complete tasks to the relaxed kick-back mode when enjoying music, movies, alone time, or other people. While a beer or mixed drink serves that role for many, many others may prefer marijuana which doesn’t leave a hangover or, for alcoholics, trigger a lapse.

Marijuana

There are no recorded, verifiable cases of a fatal human overdose from marijuana alone. Cannabis (marijuana) produces various physical and mental effects by acting on brain receptors, commonly causing euphoria, relaxation, and heightened sensory awareness. Short-term, it can impair memory, motor skills, and judgment, with risks including anxiety, panic, or psychotic symptoms. Long-term effects may include respiratory issues, cardiovascular strain, and dependence.

Despite fluctuations, marijuana use rose from 10.17% in the 1990s to 17.81% from 2010-2017. A 2021 study using U.S. data found that in some states (e.g., Colorado), legal recreational cannabis was associated with a 13% average monthly decrease in the purchase of all alcohol products, with wine sales showing a 6% decrease. A 2024 survey indicated that 36% of U.S. cannabis users reported drinking less alcohol. Legalization, particularly of medical marijuana, has been linked to a 15% decrease in monthly alcohol sales, specifically beer and wine, in legalizing counties compared to control counties. Some studies show that legal cannabis access is associated with a decrease in alcohol-related traffic fatalities. Recent 2025 research indicates that following the opening of retail cannabis stores, alcohol use declined among young adults (18–29), and binge drinking frequency decreased among adults aged 50–59. Some studies suggest that since alcohol is a common factor in violent crime, the substitution of cannabis for alcohol may contribute to a reduction in violent crime rates.

Cannabis cannabinoids (like THC and CBD) bind to the same natural, endogenous cannabinoid receptors CB1 and CB2 that exist naturally in the human body. There are natural cannabinoids our bodies naturally use to regulate functions like mood, memory, sleep, and pain. These receptors are part of the endocannabinoid system (ECS), which is widespread throughout the brain and body.

Coca

Coca leaves, traditionally used in the Andes to combat hunger, thirst, and fatigue, act as a mild stimulant similar to strong coffee. They are rich in nutrients, aid with altitude sickness, and are used for cultural/religious purposes. While generally safe in traditional, low-dose, unprocessed forms, they can still cause positive drug tests. There are no data on possible deaths due to coca leaf use. Although the leaves are used to treat common ailments and boost energy every single day, it has been found that regular use is nothing but a cultural habit, and is not addictive, harmful or mind-altering, unlike cocaine.

Indigenous peoples of South America have used coca leaves for at least 8,000 to 10,000 years. Archaeological evidence, including findings in Peru’s Nanchoc Valley, confirms that early Andean societies integrated coca into their cultures for medicinal, religious, nutritional, and social purposes long before the rise of the Inca Empire. Cocaine was first isolated from coca leaves in 1855 by German chemist Friedrich Gaedcke, who named it “erythroxyline.” It was later purified in 1859-1860 by Albert Niemann, who gave it the name “cocaine.”

Cocaine is a powerful, highly addictive stimulant drug that acts on the central nervous system to produce intense, short-lived feelings of euphoria, high energy, and mental alertness. It works by causing a massive buildup of dopamine in the brain’s reward circuits, while also constricting blood vessels and increasing heart rate. The effects are generally divided into immediate (short-term) and long-term consequences, both of which carry significant health risks. Before the widespread influx of illicitly manufactured fentanyl (roughly prior to 2013-2015), the cocaine-involved overdose death rate in the U.S. was significantly lower and relatively stable, often fluctuating between 1.3 and 2.5 deaths per 100,000 population. As fentanyl entered the market, the rate began rising by about 27% annually starting in 2013, surpassing the 2006 peak by 2016 and reaching 7.3 per 100,000 by 2021. Approximately 79% of cocaine-involved overdose deaths also involve opioids, mainly synthetic opioids like fentanyl, which is the primary driver of the increased death rate. Legalizing cocaine with requirements for product purity, the cocaine death rate would once again drop to its low baseline of pre-2013.

At the extreme end of the stimulants, methamphetamine (meth, also called crystal, chalk or ice) is an addictive stimulant that can be administered orally, smoked, snorted or injected. Smoking or intravenous injection delivers meth to the brain rapidly, resulting in immediate and intense euphoria. Meth use is associated with severe neurological and physical consequences (e.g. paranoia, violent behavior, psychosis, anxiety and depression) and has become a serious public health problem worldwide. The age-adjusted rate was 8.5 deaths per 100,000 population.[18]

In the family of synthetic stimulants:

Methamphetamine (Crystal Meth): Often considered more powerful and addictive than cocaine, methamphetamine releases significantly more dopamine in the brain and has a much longer-lasting high (12–14 hours compared to 1 hour for cocaine). It is generally considered the strongest stimulant available, providing a longer, more intense, and faster-acting addictive effect.

Desoxypipradrol: Research indicates this compound, found in some “legal highs” is more potent than cocaine in causing dopamine release and slowing dopamine re-uptake, with studies suggesting a sevenfold increase in dopamine levels compared to three times for cocaine.

MDPV (“Bath Salts”): MDPV acts similarly to cocaine by inhibiting dopamine re-uptake but is reported to be nearly 10 times more potent, providing a much stronger, uncontrollable high. “Bath salts” is a slang term for this dangerous, lab-made synthetic cathinone (a naturally-occurring stimulant monoamine alkaloid found in the khat shrub (Catha edulis), chemically similar to amphetamines and ephedrine) and are central nervous system stimulants designed to mimic the effects of illegal drugs like cocaine and methamphetamine.

Opiates

The poppy’s offering for human use began as early as 5000 BCE in the Neolithic age, with the oldest archaeological evidence found in the Mediterranean region. Seeds from this era suggest it was used for food, rituals, and early medicinal purposes. It was later documented in ancient Egyptian, Greek, and Roman medical texts. The plant’s chemistry has moved from the most basic form of flower pod gum named opium (dried latex obtained from the seed pods of the opium poppy) to morphine, developed in 1804 through a process involving harvesting raw opium, followed by chemical extraction and purification to isolate morphine from other alkaloids like codeine, which was developed in 1832 and touted as a ‘cure’ for morphine addiction.

Heroin was first synthesized in 1874 by C. R. Alder Wright from morphine. It was later commercialized by the Bayer pharmaceutical company in 1898 as a cough suppressant and pain reliever, widely marketed as a non-addictive alternative to morphine before its addictive nature was fully understood, leading to its eventual strict regulation. Thereafter, numerous semi-synthetic and synthetic opioids were developed, largely in the 20th century, to provide pain relief with the hope of reducing addiction potential. Key opioids developed after heroin include:

Methadone (1930s-1940s): Developed in Germany, this synthetic opioid is used for pain management and to treat opioid use disorder.

Meperidine (Demerol) (1930s): The first synthetic opioid, designed to be a safer alternative to morphine.

Oxycodone (OxyContin/Percocet) (1916): While synthesized shortly after heroin, it gained widespread prominence in the late 20th century, particularly with the 1996 release of OxyContin.

Hydrocodone (Vicodin) (1920s): A semi-synthetic opioid created from codeine.

Buprenorphine (1960s): Developed as a partial agonist for pain and later approved in 2002 for the treatment of opioid addiction.

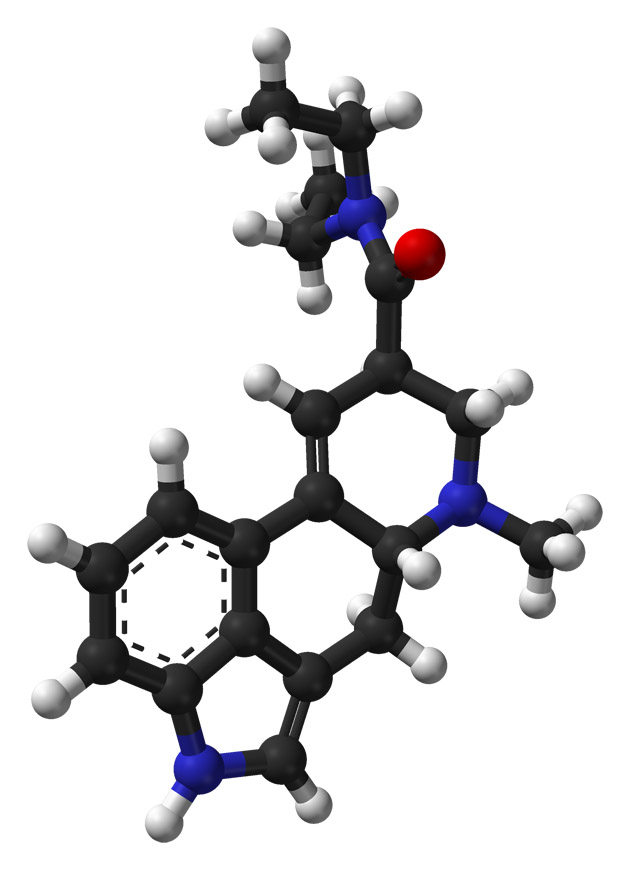

Fentanyl (1960): A highly potent synthetic opioid, roughly 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine, developed for surgical anesthesia and pain management. Its extreme potency makes the risk of fatal overdose significantly higher than that of cocaine, especially since it is often found as a contaminant in other illicit substances. It is less expensive than natural opioids because it is made from synthetic substances whereas natural opioids depend on poppy production.

Opiates exert their main effects on the brain and spinal cord. Their principal action is to relieve or suppress pain. Like all opiates, opium causes a pleasant, drowsy state, in which all cares are forgotten and there is a decreased sense of pain (analgesia). Immediately after injection, the feelings are most intense. This feeling is described as similar to a sexual orgasm. The drugs also alleviate anxiety; induce relaxation, drowsiness, and sedation; and may impart a state of euphoria or other enhanced mood. In the body, opiates also have important physiological effects; they slow respiration and heartbeat, suppress the cough reflex, and relax the smooth muscles of the gastrointestinal tract. Opiates are addictive drugs–i.e., they produce a physical dependence (and withdrawal symptoms) that can only be assuaged by continued use of the drug.

Long-term opium use is associated with a significantly increased risk of death from nonmalignant respiratory diseases (such as COPD, asthma, and pneumonia) and cardiovascular disease. In one study, opium consumption was significantly associated with increased risks of deaths from several causes including circulatory diseases (hazard ratio 1.81) and cancer (1.61). The strongest associations were seen with deaths from asthma, tuberculosis, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (11.0, 6.22, and 5.44, respectively).[19]

The most powerful synthetic opiate invented so far is fentanyl. Similar to other opioid analgesics, fentanyl produces effects such as: relaxation, euphoria, pain relief, sedation, confusion, drowsiness, dizziness, nausea and vomiting, urinary retention, pupillary constriction, and respiratory depression. Death rates for fentanyl are 14.3 deaths per 100,000 standard population in 2024, marking a significant 35.6% decrease from the 2023 rate of 22.2. Despite this recent decline, fentanyl remains the dominant driver of fatal overdoses in the U.S., involved in roughly 60% to 70% of all drug overdose deaths.

Hallucinogens

Not mentioned so far are the hallucinogens, primarily LSD, peyote/mescaline, psilocybin, salvia, and DMT/Ayahuasca. Considered sacramental to many, use of these drugs can lead to spiritual insights, so-called “mystical” experiences such as the sense of “pure” being, the sense of unity with one’s surroundings, the sense that what one experienced was real, and the sense of sacredness. There are similarities between psychedelic experiences and non-ordinary forms of consciousness experienced in meditation and near-death experiences. The phenomenon of ego dissolution is often described as a key feature of the psychedelic experience.

Ancient religions used various plant-based hallucinogens (entheogens) for rituals, including Soma in Vedic Hinduism circa 1500 BCE, psilocybin mushrooms and morning glory among the Maya/Aztecs circa 3000 BCE, Tabernanthe iboga in African Bwiti, and Datura by Mississippian cultures. These substances were used to achieve ecstatic states, connect with deities, and induce prophetic visions. Some scholars argue that early Christian, Roman-Egyptian, and Greek rites used psychoactive substances in their sacraments.[20]

Users typically report seeing colors, patterns, and shapes that are not real, such as complex, moving geometric patterns (fractals), or trails/tracers behind moving objects. Other effects range from Sensory Confusion (Synesthesia),acommon experience where senses blend, such as “hearing colors” or “seeing sounds”; Time and Space Distortion: Perception of time can slow down significantly, speed up, or seem to stop; and Self-Identity Alteration: Users may experience “ego dissolution,” where the boundary between self and the external environment becomes blurred, sometimes leading to a feeling of becoming one with their surroundings.

Multiple studies suggest psilocybin can produce rapid, substantial, and long-lasting antidepressant effects, sometimes for as long as six months to a year after just one or two doses. The FDA has granted “breakthrough therapy” designation to psilocybin for both conditions to expedite research and development. Psilocybin has shown efficacy in reducing anxiety and distress in patients with life-threatening conditions, such as cancer, promoting improved quality of life and well-being. Pilot studies for alcohol use disorder and tobacco addiction have demonstrated promising success rates, with some participants achieving long-term abstinence. The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) is funding a multi-site study on its effectiveness for tobacco addiction. Research is also exploring its potential for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and cluster headaches, with encouraging initial results in small studies.

First time users of hallucinogens are best served by exploring the experience in the company of an experienced user. Best results with hallucinogens would occur when the user is not under the influence of alcohol or any other drug. He/she should remain for the duration in a safe, comfortable space with no unexpected interruptions. Since the effects of LSD, for example, take at least 1-2 hours to gradually come into force, then continue to rise for 3-4 hours, then linger for up to another six hours, the user should pay attention to periodic refreshment with water. Generally the user will experience no appetite for food. The experience can be unsettling if the subject is trying to interact with the public or large crowds, or if the experience is initiated when the subject is already tired or not feeling well. These nuances of the psychedelic experience with any particular drug are why first time users benefit from being accompanied by a trusted, experienced user.

Tobacco and Alcohol

Not mentioned in the discussion so far are tobacco products. Known to be carcinogenic, tobacco is credited with 490,000 deaths per year in the United States. This is more than all illegal drugs and alcohol combined at total of 278,000—80,000 to 100,000 per year from currently illegal drugs and 178,000 from legal alcohol use. However, there is evidence that pesticides and other chemicals contribute to tobacco-related deaths, both for smokers and for agricultural workers who are directly exposed during farming.[22] However, no research to date is found showing less harm from organic tobacco.

Different policy approaches to these various substances is a combination of tradition and risk of collateral damage in those who abuse the substance. For example, tobacco has been popular in its various forms of usage for over 600 years in Western cultures, although indigenous peoples have used it over 10,000 years. Aside from the real damage caused by second-hand smoke, there is no perceived risk to others from its use.

Nicotiana tabacum was used traditionally for wide range of disorders, it administered externally for bites of poisonous reptiles and insects, pain, neuralgia, gout, to enhance hair growth, in the treatment of ringworm, ulcers, wounds, and as respiratory stimulant. It is the nicotine that causes smokers to become addicted to tobacco, and the chemical itself is lethal in small doses. When tobacco smoke is inhaled, the nicotine passes quickly to every organ of the body. The brain and nervous system are stimulated by small doses and depressed by larger ones.

Alcohol use, on the other hand, with the earliest chemically confirmed, recorded use dating to approximately 7,000–6,600 BCE in Jiahu, a Neolithic village in China’s Yellow River Valley, has several legitimate, modern medical uses, primarily as a topical antiseptic-disinfectant (hand sanitizer, skin prep), an ingredient in pharmaceuticals, and an agent in specialized procedures like nerve ablation or cyst sclerotherapy. Historically used for pain and sedation, it is not recommended for systemic consumption and been linked to liver disease, heart problems, and certain cancers. Alcohol can cause brain damage, especially with chronic use.

Alcohol adversely affects behavior in some users, leading to problems like drunk driving and negative behavior including:

- Intimate Partner and Family Violence: Alcohol is present in a significant percentage of domestic violence incidents, often increasing the severity of the abuse.

- Assault and Battery: Impaired judgment and increased aggression frequently lead to physical altercations, including aggravated assault.

- Sexual Assault: Alcohol use by both perpetrators and victims is frequently observed in sexual assault cases, where it can suppress inhibitions or affect risk perception.

- Homicide: Alcohol is highly correlated with violent crimes, including homicides.

- Property Crimes: Impulsive decision-making and reduced consequences-awareness can lead to crimes such as robbery, theft, and vandalism.

Alcohol is highly addictive because it acts on multiple neurotransmitters, slowing down the nervous system while releasing a surge of dopamine. Alcohol addiction withdrawal can be fatal, requiring professional, medical supervision. But modern medications like Xanax and Valium, designed to treat anxiety, also are highly addictive, causing severe physical dependence and dangerous withdrawal symptoms. Considered a behavioral “addiction,” gambling stimulates the same reward circuits in the brain as drugs, driven by the anticipation of reward and risk. Addictions to high-sugar or high-fat foods can trigger intense cravings similar to drug addictions. Most recently, technology (Internet/Social Media) has been determined to be addictive, characterized by compulsive use driven by dopamine hits from social interaction and instant gratification.

But What About the People?

In order to fulfill the promise offered by the end of prohibition, we as a society must accept that each individual is responsible for his/her own well-being. The state is not a parent who must watch over and discipline its children. By declaring drugs, drug dealers, or Satan, or any other phantom as the ‘reason’ someone uses drugs, we take away that individual’s agency as a human being while assigning responsibility to an invisible non-entity that no one controls. By taking away a person’s direct responsibility for his or her problems, we render them helpless. This is, sadly, a mantra for Alcoholics Anonymous, which states “We admitted we were powerless over alcohol — that our lives had become unmanageable.”

This mindset is criticized by many for the following reasons:

- Undermining Self-Efficacy and Agency: Critics argue that constantly reminding individuals that they are fundamentally powerless can damage their belief in their own ability to change. This loss of self-efficacy—the belief in one’s capacity to succeed—can lead to a fear of attempting to change behaviors independently.

- Encouraging a “Victim” Mindset: By emphasizing that the individual is powerless against a disease, it may become easier for them to deflect blame for their actions, leading to a mindset of helplessness.

- Self-Fulfilling Prophecy of Failure: The belief that “I am powerless” can become a self-fulfilling prophecy. Critics contend that this mindset, combined with an “all-or-nothing” approach to sobriety, can cause individuals to abandon recovery entirely after a single relapse or slip-up.

- Disempowerment vs. Empowerment: Instead of promoting empowerment, some argue that the focus on powerlessness can be psychologically damaging, negatively impacting self-esteem by forcing individuals to define themselves as broken or lacking control.

- Discounting Personal Responsibility: A major criticism is that the focus on powerlessness can lessen the urgency to take personal responsibility for one’s actions, which many believe is a cornerstone of behavioral change.

- Potential for Shame and Despair: The requirement to admit total defeat, or “hit rock bottom,” can plunge individuals into intense shame, guilt, and despair rather than providing an immediate sense of hope.

Other programs that adhere to this 12-step concept are Narcotics Anonymous (NA), Cocaine Anonymous (CA), Crystal Meth Anonymous (CMA), Marijuana Anonymous (MA), Gamblers Anonymous (GA), Overeaters Anonymous (OA), Sexaholics Anonymous (SA), plus Al-Anon and Nar-Anon, programs for families and friends. (Clearly addictive behavior is not limited to illegal drugs) Success data for these programs is not encouraging: Long-Term Abstinence: 5% to 10% of participants achieve long-term, sustained sobriety. Some studies have shown that 50% to 70% of those who attend weekly or near-weekly meetings maintain abstinence. AA’s own surveys have indicated that approximately 35% of members have been sober for more than five years. Evidence-based treatments like Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and medication-assisted treatment (MAT) often yield higher success rates, with some studies showing 60% abstinence after one year of therapy.

In a 2011 study, the cumulative probability estimate of transition to dependence was 67.5% for nicotine users, 22.7% for alcohol users, 20.9% for cocaine users, and 8.9% for cannabis users. Half of the cases of dependence on nicotine, alcohol, cannabis and cocaine were observed approximately 27, 13, 5 and 4 years after use onset, respectively.[23] In comparison, approximately 14% to 20% of U.S. adults are estimated to have an addiction to highly processed foods. This condition, which involves compulsive eating behaviors similar to substance abuse, is higher in specific groups, including up to 28% of adults with obesity and roughly 13% of adults aged 50–80. Roughly 3% to 11% of the U.S. population may experience issues related to pornography addiction, with studies indicating a higher prevalence among men. Approximately 3% to 5% of Americans experience some form of gambling-related harm. Estimates suggest that approximately 3% to 6% of the U.S. population may suffer from sex addiction or compulsive sexual behavior, affecting roughly 10-20 million people. Some research indicates this figure may be as high as 8.6% to 10%, with men being more frequently affected than women.

Pricing Legalized Drugs

Upon purging U.S. policies of the drug war, prices for legalized natural intoxicants (marijuana, coca leaf, opium gum) should be substantially lower than for legalized refined products like cocaine or opium derivatives such as morphine and codeine. This type of pricing reflects the relatively less harmful effects of the naturally-occurring material. Currently, forty states (80%) have legalized marijuana for medical use and twenty four states (48%) have legalized for recreational use. As of early 2026, the price range for a gram of recreational marijuana typically falls between $3 and $20, with the national average often hovering around $10–$15. The price varies significantly based on state, quality (budget vs. premium), and market maturity. In states where marijuana remains illegal, the price per gram in early 2026 typically ranges from $10 to $20, with some premium or highly restricted areas seeing prices reach up to $50 per gram. In current commercial grades of marijuana, THC (tetrahydrocannabinol) can range from less than 10% up to 30%. One time dose for 20% THC content, with one puff delivered either from a “joint” or in a pipe and containing .32 gram, will be felt almost immediately and last 1-3 hours.[24]

Oregon (2020) and Colorado (2022) have legalized or decriminalized the supervised use of psilocybin. In those states, a 1-2 hour micro-dosing session may cost around $500. A complete psilocybin-assisted therapy session, which can last up to six hours and includes pre- and post-session consultations, typically costs between $1,000 and $3,000, and sometimes more. Multi-day, immersive experiences offered by some companies can cost between $4,000 and over $7,700. Street prices for psilocybin mushrooms range from one gram for $5 – $12, one-eight ounce (3.5 grams) $32 – $35, and half ounce (14 grams) for $100 – $120. Two to three grams is considered an average dose. Dried mushrooms taken at doses between 2.5 grams to 5 grams will induce classic psychedelic experiences with kaleidoscope visuals whether eyes are closed or open, sensory and perceptual changes, synesthesia (like hearing colors or tasting sounds), cognitive changes, and ego dissolution.

That pricing policy would put the least harmful drugs in the most available price range for persons self-medicating or for recreational use. A level higher in concentration and cost for opium derivatives would be one or more of hydrocodone, hydromorphone, oxycodone, oxymorphone, nalbuphine, naloxone, naltrexone, buprenorphine, and etorphine. Similarly, cocaine’s further refinement is crack cocaine. Pricing should reflect the risk.

By making currently illegal substances available in the same type of setting as alcohol or tobacco, each person is left to choose what/how much of a substance they will obtain, if any. That individual is then directly in charge of his/her life in the most meaningful way. Instead of being treated like a child with permanent governmental parents, he/she is treated as an autonomous adult who faces life with full awareness that choices made are his/her responsibility. With this level of autonomy, an individual must decide if he/she is ready to face death as a possible result of his/her choices. We as a society absolutely must grant each person this responsibility and accept that some will die.

But will 100,000 die from abuse of these substances, as are currently? Possibly. Possibly not. Since fentanyl is responsible for up to 80% of current overdose deaths, regulated drugs sales with product testing for purity would eliminate most of these deaths since it is the adulteration of popular drugs like cocaine and other drugs with cheap fentanyl that causes most overdoses. Illegal dealers add fentanyl because it is cheaper to produce and easier to smuggle than traditional drugs, allowing traffickers to significantly increase their profit margins. Because fentanyl is roughly 50 times more potent than heroin and 100 times more potent than morphine, small, easily hidden amounts can mimic the effects of larger quantities of other substances. Other potentially adulterated drugs are methamphetamine; pills sold illegally and made to look like legitimate medications (such as oxycodone, alprazolam, or amphetamine salts); and substances like MDMA and illicitly-obtained benzodiazepines.

All we can do in a just and empathetic nation is provide options. The choice must be made by each person. No one can claim that current policies are working. Clearly the drug war has failed. Illegal drug use has shifted from a primarily recreational, counterculture phenomenon in the 1970s to a more dangerous, high-potency, and widespread crisis today, characterized by a massive increase in synthetic drug prevalence and overdose deaths. While past-month illicit drug use among Americans age twelve or older increased from 25.4 million in 1979 to 47.7 million by 2023, the nature of these drugs also has changed, leading to a six-fold increase in drug-related deaths over the past two decades. Mortality from drug overdoses has grown exponentially since 1979. Between 1980 and 1995, adult drug arrests increased by 173% and juvenile arrests by 73%.

As to lethality of illegal drugs, keep in mind that deaths due to drugs bought and sold in high-risk environments without any assurance of dose strength or purity equal half the deaths from legal alcohol and a quarter of deaths from legal tobacco.

Moral Failing?

Instead of taking a punitive approach to potentially harmful behaviors, whether drug abuse, alcoholism or overeating, why shouldn’t we try a more loving approach? Centuries of religious judgment have deemed addictions a moral failing, yet modern research has shown that measurable physical, emotional, and mental elements drive addiction. Addiction in no longer considered a moral issue, but rather a medical ‘disorder’—specifically a chronic, relapsing brain disorder—because it involves functional, long-lasting changes to brain circuits responsible for reward, stress, and self-control. It is classified as a medical condition because, like heart disease or diabetes, it disrupts the normal, healthy functioning of an organ (the brain), has serious harmful effects, and is preventable and treatable.

Yes, persons under the influence of certain drugs, primarily alcohol and stimulants like meth, can exhibit disruptive behavior. For alcohol, such behaviors can include aggression and hostility where individuals may become argumentative, confrontational, and misinterpret social cues, perceiving innocent actions as provocations. Drunkenness can cause extreme mood swings, ranging from intense, irrational anger to profound sadness, depression, or loneliness. Impaired decision-making leads to dangerous actions, such as driving while intoxicated, risky sexual behavior, or initiating fights.

For persons using meth, users may display erratic, violent, or aggressive behavior, including rage and temper tantrums. Methamphetamine is strongly associated with a wide range of criminal behaviors, acting as a catalyst for violence, property crimes, and drug-related offenses. The drug’s effects—including intense paranoia, hallucinations, insomnia, and aggression—often lead users to commit crimes, while its high addiction potential drives theft and trafficking to fund the habit. The primary reason for meth use (or other stimulants) is the powerful, immediate rush of euphoria and sense of well-being that meth provides. Users may seek increased energy, alertness, concentration, and confidence to perform better at work, school, or in social situations. It is also sometimes used to enhance sexual performance and stamina during “sexual marathons.” Meth is relatively inexpensive and easy to produce (illicitly), making it readily available in many communities, particularly compared to other stimulants like cocaine.

Unlike stimulants, benzodiazepine drugs and opiates of all stripes create a sense of pleasure. This effect is largely due to these drugs trigger the brain’s powerful reward centers and release endorphins. As a powerful opioid, fentanyl can produce strong feelings of euphoria, happiness, and relaxation.

How We Got Here

The U. S. National Institute on Drug Abuse gave the following reasons for substance use: To Feel Good (Hedonism)—to produce intense feelings of pleasure, euphoria, relaxation, or to get ‘high’; To Feel Better (Self-Medication): Individuals may use substances to cope with stress, anxiety, depression, trauma, or emotional pain. It is a common, though temporary, way to manage mental health conditions or escape life’s problems; To Do Better (Performance Enhancement): Some use stimulants (like Adderall or cocaine) to improve focus in school or at work, increase alertness, boost energy, or enhance athletic performance; To Fit In (Social Pressure): Particularly common among teenagers, individuals may use substances to conform to a peer group, feel accepted, or out of curiosity; Because of Addiction (Compulsion): Individuals may continue to use drugs to manage dependence, avoid withdrawal symptoms, or “get through the day”; Specific Needs: Sleep: To help fall asleep or treat insomnia; Weight Loss: To reduce appetite; Pain Relief: To manage physical pain.

But is that all? Or even the real issue? Yes, some of these reasons seem valid. But all of the answers fail to mention a major underlying cause: the modern age. These substances have been around for thousands of years and were used by cultures as far-flung as India and the (now) American Southwest. Historically, cannabis was first cultivated around 12,000 years ago in East Asia during the early Neolithic period. While evidence of its use dates back to 8800–6500 BCE (Before Current Era), the oldest written record is from Greek historian Herodotus (c. 440 BCE), who described Scythians using cannabis in steam baths. A 3rd millennium BCE text mentions its use in China, and a 2459-2203 BCE grave in the Netherlands contained cannabis pollen, suggesting use as a painkiller. It was used in the Indian subcontinent since the Vedic period, roughly 1500–2500 BCE.

Or consider opium, potentially far more risky than cannabis. The earliest reference to opium growth and use is found on 8,000 year-old hardened Sumerian clay-tablets where prescriptions of opium are recorded. Records are found from 3,400 BCE when the opium poppy was cultivated in lower Mesopotamia. The Sumerians referred to it as Hul Gil, the “joy plant.” The Sumerians soon passed it on to the Assyrians, who in turn passed it on to the Egyptians. Ancient Greeks, Indians, Chinese, Egyptians, Romans, Arabs, people in middle ages, Europeans from Renaissance to now, knew opium as an ever-approved next-door medicine—a panacea for all maladies. References in the Odyssey and the Bible, and use by known leaders and minds like Homer, Franklin, Napoleon, Coleridge, Poe, Shelly, Quincy, Hitler and many more, have removed the label of immorality from its use.

Why, then, are these substances now considered a plague, with medical warnings that opiates cause fatal respiratory depression, have a high potential for addiction, and can lead to severe, long-term health complications? Why is the public advised cannabis is considered harmful due to risks of addiction, impaired brain function, and serious physical health issues? That regular use can lead to cardiovascular problems like heart attacks and strokes, respiratory issues, and mental health conditions such as anxiety, depression, and psychosis?

Clearly some recent development in human existence is involved. Yes, some of the problem can be laid at the feet of ‘modern science,’ who never met a natural substance that science couldn’t make stronger, purer, and more profitable. Most people could grow a few marijuana plants in their back yard, but the potent hybrids now widely marketed are proprietary. Plus over-the-counter sales of aspirin and other pain killers would be impacted by that free availability. Worse than the chemical manipulation of marijuana, however, scientists have, in the last century, given us opium clones up to 100 times stronger than opium, not even reliant on the poppy, with which to addict and kill thousands. In medical settings, fentanyl is often chosen over morphine for superior acute pain management due to its rapid onset of action (2–3 minutes vs. 15–30+ minutes for morphine). It is preferred for causing less hypotension (no histamine release) and having fewer side effects like constipation and nausea, making it ideal for rapid, severe pain relief in emergency settings.

But the more fundamental problem isn’t drug purity or strength increasing the risk for users. It’s modern culture itself.

The historical correlation between industrialization and drug abuse is rooted in the social, economic, and technological upheavals of the 18th to 20th centuries, which shifted substance use from traditional, localized consumption to mass-marketed, addictive, and often, harmful patterns. Industrialization created a high-stress environment that fostered addiction while simultaneously increasing the availability of substances like alcohol, opium, and later, pharmaceuticals. In the early 1800s, the push for a sober, efficient workforce drove the initial, often slow, regulation of alcohol. Increased grain production and industrial farming made distilled alcohol (especially whiskey) cheaper and more accessible. Urbanization and the grueling, rigid nature of factory work created intense stress. Alcohol became a common coping mechanism for the working class. Opium and its derivatives (morphine) were widely marketed as “miracle cures” for various ailments, leading to widespread, unintended addiction.

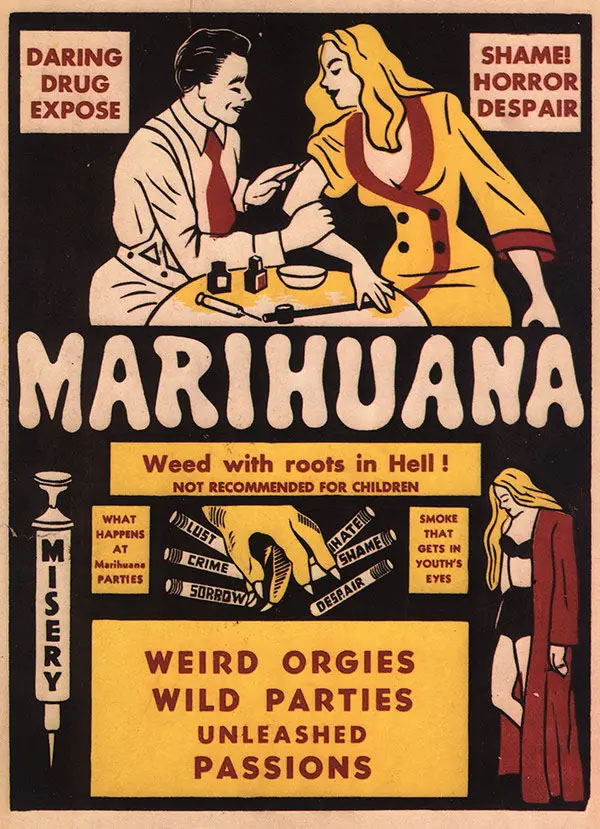

Technological advancements allowed for the refinement of stronger substances like cocaine, morphine, and heroin. The emerging pharmaceutical industry began mass-producing drugs by cloning the biochemistry of natural drugs, facilitating widespread, unregulated access to addictive substances. The industrial capacity to produce and market substances on a mass scale directly fueled addiction rates. Rapid urban migration and the loss of traditional community structures increased the reliance on pharmacological, rather than social, support. Industrialists in some contexts, such as in the U.S. South, supplied cocaine to Black laborers to boost productivity, a practice that later fueled “drug scare” propaganda when the drug was associated with minority populations. The social harms caused by increased alcohol and drug consumption during industrialization fueled major backlash, leading to the Temperance Movement and Prohibition in the U.S. (1920–1933) and similar actions in Russia, Norway, and Finland.

During World War II, governments and industries promoted amphetamines to enhance worker and military productivity. Increased global trade and transportation, essential to the industrial model, facilitated the growth of international drug trafficking. By the late 20th century, while early industrialization caused addiction through high-stress production, modern deindustrialization (the decline of manufacturing) has been linked to the recent opioid epidemic. Studies indicate that areas with high unemployment, poverty, and the loss of manufacturing jobs (“rust belts”) have experienced higher rates of addiction and overdose deaths. The erosion of middle-wage jobs has spurred economic anxiety, which is directly correlated with increased substance use disorders.

No matter what drug of abuse under discussion, the relatively recent rise in computer, internet, and smartphone use over the last two decades has occurred in tandem with increasing rates of both substance abuse and behavioral addictions (such as internet gaming or social media addiction). Research indicates that for every 10% increase in high-speed internet use, there was a corresponding 1% rise in treatment admissions for prescription drug abuse. The internet has served as a pipeline for narcotics, with increased online access correlating to higher rates of abuse for prescription opioids, sedatives, and stimulants. Digital addiction and substance addiction often activate the same brain reward pathways (nucleus accumbens/ventral striatum), with digital media providing “dopamine hits” similar to drugs. High levels of social media use (3+ hours per day) are associated with a 1.99 times higher risk of drinking and increased vaping/cannabis use among adolescents. The proliferation of screens (7+ hours daily for teens) has been linked to higher rates of anxiety, depression, and substance experimentation. There is a strong, positive correlation between the risk of internet addiction and substance use, with those using technology excessively being more likely to also engage in substance abuse.

Pre-industrial life, characterized by agrarian subsistence and localized, artisan-based economies, offered experiences now lost to modern industrialization. These pre-industrial lifestyles include extreme reliance on daylight hours, intense connection to seasonal cycles, close proximity to livestock, and deep, often isolating ties to a small, local community. Daily life was dictated by the sun and seasons, with work, food availability, and even safety, determined by nature. Most individuals lived in small, rural settlements, rarely traveling far from their birthplace, with communication limited to their immediate surroundings. For warmth and survival, people often shared living quarters or homes with farm animals, especially during cold winters. Families worked together as a unit on farms, and communities relied on localized barter systems for goods and services. Goods were hand-made by skilled craftspeople rather than mass-produced in factories, which enabled the worker to see a project through from start to finish. In most modern production, workers only see a small part of the process.

This cultural shift is the instinctive motivation behind efforts such as “Make America Great Again,” the idea that things were better “back then.” A driving force is the often mythical belief that America was superior in the past and has declined due to foreign influence and internal changes. Adherents to MAGA, as well as right-leaning conservatism around the world, point to changes such as advancements in women’s rights, immigration, increased acceptance of homosexuality, or people they see as unlike themselves (skin color, physical features) as the reasons for their outrage. But in looking back to, say, 1870, American life not only operated under white-male dominance, prison and/or death for outed homosexuals, and entrenched racism but also was a time when most families were working long hours every day to produce and preserve food for their tables and the greatest skills required were successful seed saving, animal husbandry, and fishing/hunting wildlife.

Before agriculture, the hunter-gatherer lifestyle was even less complicated as people wandered over their known habitat gathering lean meats, fish, wild fruits, vegetables, nuts, seeds, and tubers. Slowly, as the idea of agriculture spread and people gained the advantage of permanent settlements, some may have felt a distant longing for roaming to find food instead of laboring to plant and harvest. There’s comfort found in a pastoral life pattern that has been practiced for 12,000 years. With agriculture, a person knew what to expect as seasons changed and dictated the week’s agenda. But by the late 19th century, only a few in mainstream societies followed the primeval lifestyle.

As formalized in the mid-20th century rise of a philosophy of existentialism, existential dread, or existential anxiety, has created a profound, overwhelming sense of fear, anxiety, or unease regarding the meaning, purpose, and value of human existence. Often triggered by contemplating death, isolation, freedom, or the apparent lack of inherent meaning in life, it manifests as deep anxiety about one’s place in the universe. Four alienations suffered by modern mankind are tenets of this philosophy:

- Alienation from the Product of Labor: The worker creates products they do not own, which then exist as a hostile, independent power.

- Alienation from the Act of Production: Work is not fulfilling or creative but coerced, monotonous, and merely a means of survival.

- Alienation from Species-Being (Human Nature): Humans are separated from their intrinsic creative potential and consciousness, reduced to animal-like functions.

- Alienation from Other Humans/Society: Social relations are reduced to competitive, transactional interactions, breaking down community and cooperation.

Similarly, Paul Tillich (German and American Christian existentialist philosopher, religious socialist, and Lutheran theologian) conceptualized these alienations as:

- Separation of Man from the Ground of Being (Alienation from God): This is the fundamental, ontological, and religious alienation. It is the loss of the essential union between human existence and the “Ground of Being” (God), resulting in a loss of ultimate meaning.

- Separation of Man from Himself (Self-Estrangement): This involves the loss of personal center and self-actualization. Humans are split within themselves, failing to become what they essentially are, leading to existential anxiety and despair.

- Separation of Man from Others (Alienation in Social Relationships): A separation between individual lives, characterized by a lack of true community, high levels of distance or isolation, and conflicts that make mutual understanding impossible.

- Separation of Man from the World of Nature: A further consequence of estrangement, where humanity is detached from the natural world, often resulting in a desire to exploit or dominate nature rather than participate in.

Tillich’s work, particularly in The Courage to Be, provides a framework for understanding addiction as an attempt to fill the “void” of meaninglessness.

Jean Paul Sartre, another mid-20th century existentialist, famously stated, “Man is nothing else but what he makes of himself”. An addict, in this view, is constantly choosing to be an addict through their actions. His work explores the anxiety (angst) of existence, with some interpreting the “bohemian” lifestyle of intense substance use (tobacco, alcohol, amphetamines) as a way to cope with this existential weight. To maintain a rigorous, high-speed, 10-hour-a-day writing schedule, Sartre heavily used Corydrane, a mixture of amphetamine and aspirin. He reportedly took up to 20 pills a day. According to Annie Cohen-Solal, who wrote a biography of Sartre, his daily drug consumption was thus: two packs of cigarettes, several tobacco pipes, over a quart of alcohol (wine, beer, vodka, whisky etc.), two hundred milligrams of amphetamines, fifteen grams of aspirin, a boat load of barbiturates, some coffee, tea, and a few “heavy” meals (whatever those might have been).

Other 20th century notables who abused substances include Hunter S. Thompson, who was famously known for a daily, high-octane consumption of drugs and alcohol that powered his “Gonzo” journalism. His routine notoriously included cocaine, marijuana, LSD, and large quantities of Chivas Regal, Heineken, and Dunhill cigarettes, often beginning in the afternoon and continuing through the night.

Aldous Huxley (1894–1963), author of fifty books including Brave New World, was a prominent proponent of using psychedelic drugs for consciousness expansion, most famously documenting his 1953 mescaline experience in The Doors of Perception. He believed these substances provided mystical experiences and enhanced creativity, later exploring LSD and advising early researchers like Timothy Leary.

Numerous popular artists of the mid-20th century were known for their abuse of drugs and alcohol, including Elvis Presley, Marilyn Monroe, Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix, Jim Morrison, Frank Sinatra, Judy Garland, John Belushi, Billie Holiday, Truman Capote, Dylan Thomas, Philip K. Dick, Tennessee Williams, John F. Kennedy, Richard Nixon, Howard Hughes, Adolf Hitler, Jackson Pollock, Bill Wilson, and Timothy Leary.

Industrialization most severely impacted the U.S. population between 1880 and 1920, marked by rapid urbanization, massive immigration, and harsh factory conditions. During this “Second Industrial Revolution,” the population shifted from primarily rural to urban, with cities becoming overcrowded, leading to significant social and economic inequities. During that period, the United States experienced a significant, unregulated, and largely unrecognized drug epidemic, with addiction rates for opiates and cocaine comparable to, or in some estimates exceeding, modern levels. It is estimated that up to 5% of the U.S. population was dependent on drugs, with a high concentration of opiate addiction.

Fast forward to 2020 when the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), estimated that 13.5% of people aged 12 or older (37.3 million people) used an illicit drug in the past month. Not surprisingly, the digital age in the United States most severely impacted the population through a combination of rapid, transformative shifts between 1995 and 2010, with the most intense, widespread disruption occurring around the introduction of the smartphone (2007) and the subsequent rise of social media. This era shifted technology from a professional tool to an immersive, always-on part of daily life.