This morning I received a query from a friend of mine asking where he could buy one of my books. He didn’t want to buy from Amazon and further line the pockets of Jeff Bezos.

This widespread reaction to Bezos’ fortune and his choices of how to spend his money has reached the point where I feel obligated to fully explain why my books are marketed at Amazon and why we might need to take deep breath and cut Bezos a tiny bit of slack.

In 1994 at the age of 32, Bezos decided to establish an online bookselling enterprise. Within the next twenty years, his company Amazon had expanded to offer an enormous range of products. But his original idea was about books. By the early 2000s, Bezos had expanded his concept to allow authors to publish their own books.

Before this, authors faced two options. Traditionally, a printed submission letter with an outline of the proposed book would be submitted to a publishing house for consideration. If interested, the publisher would request the manuscript for review. With a slim chance of acceptance, the book could easily languish in these dead end processes for years before a) a publisher somewhere accepted the book or b) the author gave up in despair.

By the end of the 20th century, publishing houses increasingly refused this first layer of submission from authors. Instead, authors were directed to find an agent who, after screening the manuscript, might deign to take the book under his wing and offer various revisions and plot recommendations before then trying to market the book to a publishing house. The publishing house still could refuse the book, but if they saw any promise in the project, their editors would pick through the manuscript for yet more revisions. Again, months turned into years while authors held onto hope, usually to ultimately meet with rejection.

Or worse. Two books of mine submitted in the late 1990s through this Sisyphean process ended up published by other people. I’ve described these infuriating experiences of intellectual property theft in previous blog posts here, here, and here.

The other option for authors was to self-publish. This path was taken by my mother who paid nearly $2,000 for her family history to appear in print. A friend of mine also took this route when she paid a vanity press to print a few thousand copies of her book, which she had to store in her garage and distribute herself. But along with the internet and the engineering genius of Bezos, Amazon formed a branch known as Kindle Direct Publishing (KDP) where an author had total control over the publication of her/his book.

Print on demand simply means that when someone purchases a certain book, it is then printed and shipped. An author using KDP must prepare the manuscript by certain layout guidelines, but is then free to choose page size, white or cream paper, and certain other formatting options. The manuscript is uploaded at the KDP website and after proofing, the book is ready to purchase. The author can either use KDP’s cover templates to create the book’s cover or upload a cover file created entirely by the author. (I use Photoshop and thoroughly enjoy the use of color, imagery, and font choices.)

The freedom this provides an author is absolutely stunning.

A few print-on-demand enterprises co-exist with KDP, but KDP’s software is supremely user friendly and allows for maximum author flexibility. KDP also offers swift interaction with staff via email, chat, or phone if/when questions arise. KDP pricing, at least for paperbacks, means that authors gain a higher share of the sale price than is available through any other publishing outlet. Ebook pricing is not quite as competitive as a few other entities such as Smashwords, but promotional options are much wider.

My first book, Notes of a Piano Tuner, published in 1996 by a traditional small regional press, sold for $16.95. My royalty was one dollar. Through KDP, a recent book that retails for $26.95 pays me $8.70. KDP retains $7.47 for printing costs, and the rest is KDP profit. While that is a sizeable profit for KDP and its parent Amazon, I am still ahead of the 5.8% profit I received through traditional publishing. At $8.70, that’s over 32% profit.

Perhaps even more important for most authors is that self-pub books at KDP remain on their virtual bookshelves forever and essentially worldwide. These services are available to authors in India, China, Japan, and many other far flung locations and in their own language. KDP provides the services needed to register my ISBN number with the Library of Congress. They provide marketing tools I can use to promote my books. I don’t have to do anything for my books to be found in online searches for my subject matter.

While all this is wonderful and amazing and possibly would have occurred sooner or later without Jeff Bezos, the fact is that he was the one who made it happen.

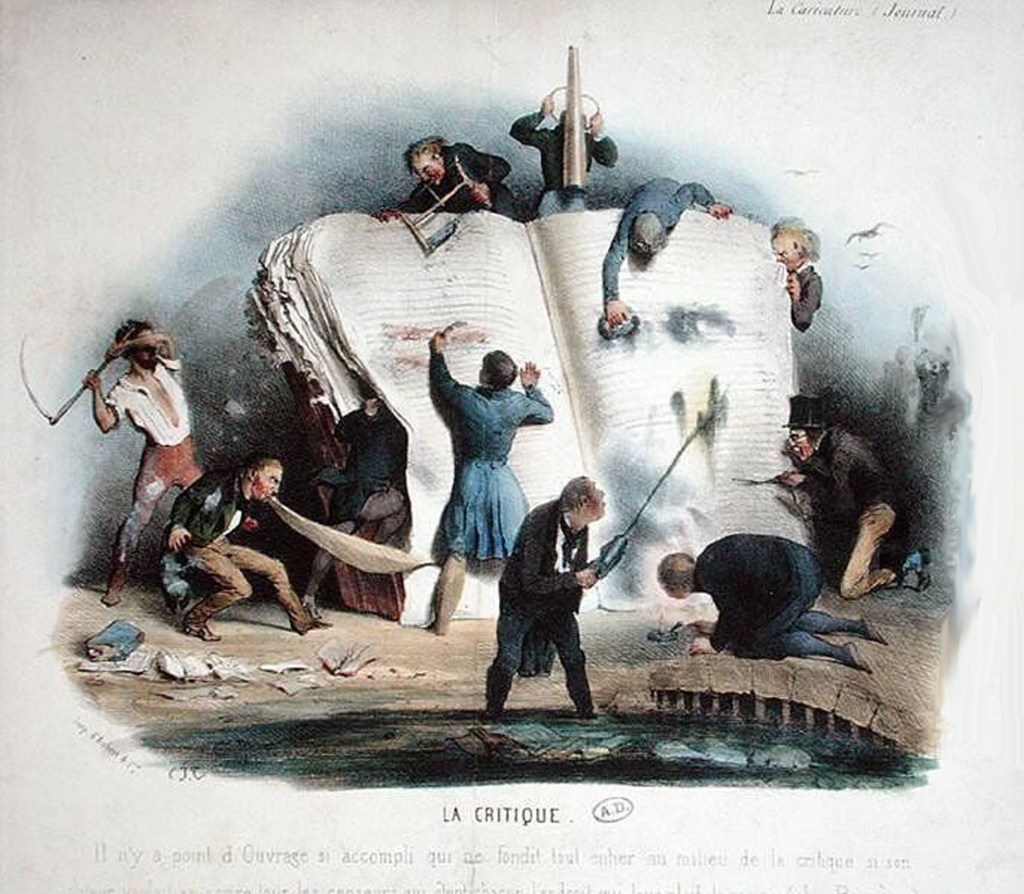

Not to say there hasn’t been a downside to the avalanche of author-published books his brain child has created. Key to the bookselling industry have been the various filters through which a manuscript would pass—agents, editors, and ultimately reviewers who offer insight into the nature and quality of any particular book, thereby providing a prospective reader a guideline of sorts to measure whether plopping down the requisite dollars is a wise decision. But as this Indie avalanche hit mainstream reviewers like Book Review Digest, Booklist, Book World, Kirkus Reviews, and Library Journal or other traditional book review sources including Saturday Review, Observer, New York Times Book Review, and The New Yorker, the welcome mat quickly rolled up.

Self-publishing authors, known as Indies (independent), suffer no such critiques either before or after publishing. Some are able to pay a few of these review entities to gain a review, but the price is steep. Kirkus, for example, wants $500 per review for the onerous task. Most turn up their noses entirely.

The reason for this bottleneck in the literary pipeline is painfully clear to anyone who reads Indie books at random. The writing can be abysmally awful, everything from misspelled words to dangling modifiers and other grammatical abominations to outright absurdity in balanced presentation or research authenticity or, in fiction, plot line or character development. Furthermore, the Indie risk of showing one’s bare behind, i.e. complete lack of literary talent, is compounded at the review stand by the sheer quantity of self-published books flooding the marketplace.

For a few genres, most notably romance fiction, a review option of sorts has sprung up to fill the gap. Facebook pages, groups, and multiple websites have proliferated where authors can submit a romance book for review. For a modest fee, usually $50 to $100, a promoter will set up review ‘tours’ that take a book through several such entities and can, in theory, rack up a nice quantity of reviews for that particular book which are then posted to the Amazon book listing page as well as to other book promotion sites like Goodreads. A rating of 5 stars is a sure path to reader interest, and most of these reviewers won’t post a review of less than 3 stars.

No such wondrous option exists for most other types of books. A few exist for science fiction, a few for historical fiction, but virtually none for nonfiction. Authors must find creative ways to let the public know about their books, which up to a few years ago could include setting up an author page on Facebook alongside a personal page. One author I know had gained nearly one thousand ‘followers’ on her Facebook author page, and each time she published a new book or wanted to promote an existing book, she simply posted an enticing bit on her author page and the majority of her followers would receive the notice on their newsfeed.

Sadly, those days ended with Facebook’s corporate rush for money. Now my friend’s author page posts are seen only by a half dozen or less of her followers. The only way she can make a bigger splash is to pay Facebook to promote her posts. Depending on her choice of audience, the number of days the post should run, and her spending limit, Facebook will promote the product. It has reached the point, however, where Facebook newsfeeds are so spammed with similar “sponsored” ads that people usually just scroll past.

Ironically, even traditional publishing has stopped most expenditures on book promotion. Publishing is less about literary accomplishment and more about profits, and the trimming has proceeded at pace. Authors whether Indie or not are expected to pay their way through book signing tours and public appearances.

Despite these stumbling blocks in Indie publishing, the old publishing world has crumbled. Few corporate-owned publishers are willing to risk possible low returns on an investment of manpower, ink, warehousing, and distribution unless the odds are good that an adequate return is more or less guaranteed. That’s why books by celebrities and known authors crowd the shelves and why libraries, which depend on mainstream reviews to determine acquisitions, will rarely if ever shelve Indie books.

In my case, where the majority of my books are focused on local history, I can promote my books through networks of friends and in local outlets. In the case of the book my friend wants to purchase, Good Times: A History of Night Spots and Live Music in Fayetteville, Arkansas, the demand has been great enough that I have partnered with the Washington County Historical Society to serve as an outlet through which they gain a decent percentage of the sale price and which offers the interested public a local source for the book.

However, the book is still published by KDP. As the author, I pay only the printing cost and receive no royalty from the sale. Whatever margin I wish to receive is gained in the wholesale price I charge the historical society. But, simply put, that and the rest of my books likely would not exist without Bezos.