Over a period of weeks, sometimes months, my dad would collect bits of debris to burn in the big garden beside their house in town. At the edge of the dormant garden, he would back up to his growing stack of brush, the bed of his rusted blue Ford Ranger piled high with dead limbs and old fence posts and oddly shaped pieces of wood that he might find alongside the road. The truck unloading was ceremonial, it seemed to me one day when I watched him, a kind of ritualistic process where he lifted each piece from the truck, carried it slowly in his now-halting pace across the soft, plowed dirt, and strategically placed it on the rising, unruly mound. Even the very last, tiny pieces merited his attention, scraped from the truck bed with his worn-out broom and thrown in fistfuls onto the top of the pile.

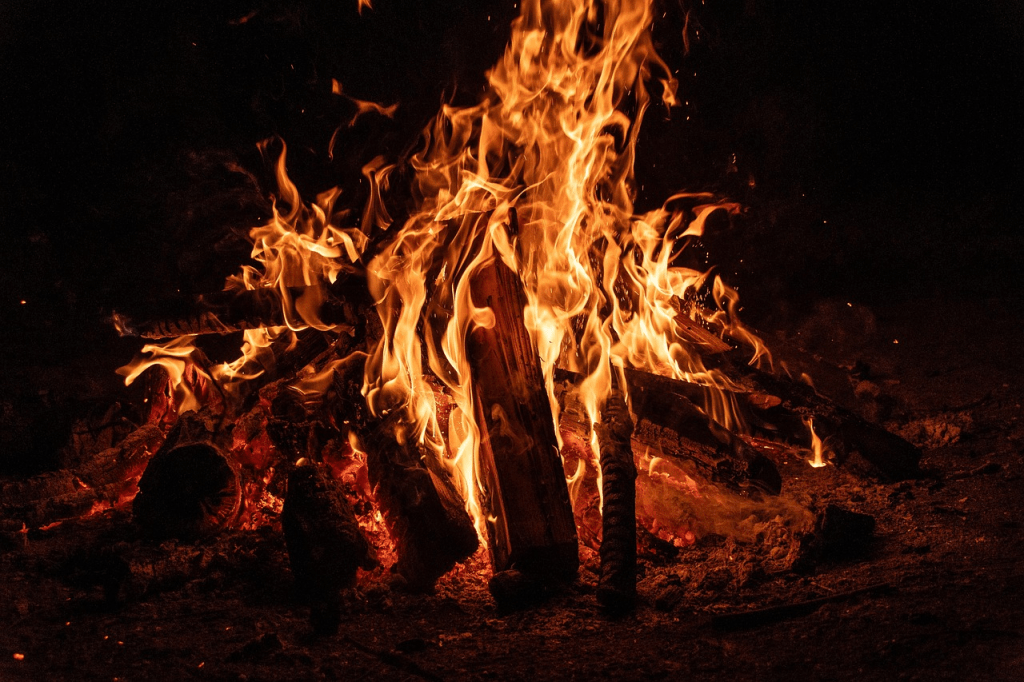

Sometimes I watched my father with his fires. Early into the process, he studied the future shape of it, how high it would blaze, whether the base would attract a good draft, whether unwanted combustibles had been suitably removed from the perimeter. He stacked his fuel accordingly, bits of wood and old lumber and limbs broken in winter storms, piled akimbo with large against small, thick against thin in a perfect formula for flame.

He would light it in the morning, when his footsteps tracked rich green across the silvery coat of dew on the lawn. His time at the donut shop for six a.m. coffee with the old liars, as he called them, would be cut short for the fire.

Usually he stood to the side of the shimmering heat, shovel in hand. After one of the last fires, my mother complained that he stood so close that the skin on his forehead turned red and later peeled. Standing in the dining room with them, I looked at my dad as she pointed out the damaged skin. He raised his eyebrows and smiled, offering no excuse except to agreeably remark that it had been hot.

I know his mind traveled to his past while he watched the fire. The flames would dance and reflect in his eyes while he talked about fields they had burned when he was growing up, his dad, his brothers, and how the mules had to plow a line around the field to keep the fire from jumping the fence. He remembered his mother and how she burned off her garden in the winter, leaving the ground filmed in ash for the early planting of onion, cabbage, and potato. He talked about the cold of the night, when the feather bed kept him warm until his father got up to build a fire the stove and his mother would mix biscuits.

A friend once remarked on the task of clearing out the old family house after his grandmother died, particularly the basement. It seems during her waning years, she had stockpiled kindling carefully gleaned from her wooded yard. Grocery sacks and cardboard boxes, each one stuffed with dried twigs and broken limbs, filled the space like so many sockets in a wasp’s nest. She had prepared a hive of future warmth. He said it took seven pickup truck loads to remove her cache of carefully prepared comfort.

At first, I discounted my friend’s grandmother’s collection of kindling as some kind of mental or emotional disorder. But today, as I picked up fallen oak twigs in my own yard, the wind tearing through the woods glowing orange with autumn, I thought about this wealth of fuel and one of the more opportune swaps in my life—my old refrigerator for a wood cookstove.

Neighbors had inherited the stove when they bought the old house down the road from me. A “Royal” brand, its heavy cast iron top features six burner plates and a water warming bin on the right. There’s a small firebox and ash bin on the left and an oven in the middle. The sides and front are white enamel, and a glass-covered chromed dial on the oven door features a double-ended needle which simultaneously points to a number and a description of the temperature: slow, warm, medium, hot, and very hot, the intervals also marked at the other end of the needle at 100, 200, up to 600.

I pick up more dead wood and stack it by the door, worrying that my bundles of twigs will be similarly disparaged someday, a burden requiring disposal by patient descendants. But I must plan for future winters when ice coats the electric lines and snow piles up on the roads and I end up with several days of splendid isolation, maybe without running water or the benefit of electricity. Then the old cookstove will spring to life, its grate glowing in a steady bed of coals, lids jiggling as food simmers on its top, the rocked chimney a beacon of warmth into the gray sky outside my window where wind will whip streams of smoke into the icy mist. In a bad winter, a person might need a basement full of kindling.

But I suspect it is not completely the need for fire that pushed my friend’s grandmother or my father in their almost religious attendance to the needs of fire. As much as they might have needed the bodily comfort the fire would assure, they had a greater, more present need—the need to accomplish. In my father’s later years, he could not show much to account for the hours of his days. But he could still build a superior fire.

When he was eighty-five and suffering mini-strokes that, he said, was like hearing distant music, we had taken away his truck keys and he couldn’t go for donuts with the old liars or gather wood for a fire. I found him one day by an old wood pile at the side of his house. He had the sledge hammer in one hand, gripped up close to the head, and a foot-diameter length of oak sitting upright on a nearby stump. He had driven a splitting wedge into the center of the oak, sweat pouring off his forehead, his slight frame bent to the task.

In response to my concerned questioning, he replied: “The ole dad is still worth something.”

I turned away so he couldn’t see my tears.

~~~

Back when his neighbor Cotton was still alive, my dad would call out to him on the morning of a fire.

“Come on over,” he’d wave his arm.

And Cotton would bring over a few limbs he’d been saving or anything wooden he wanted to get rid of, set up his lawn chair next to Dad’s, and they’d tend the fire together. Dad would stick his cigarette lighter down to the bits of paper and cardboard he had crumpled at the base of the heap, and then light a fresh Winston and draw on the cigarette strong and deep while the blaze flared into the brush and started working its way up the near side of the pile.

The fire merited their full attention. Orange-red flames would tear through the heap of wood, picking up speed. They listened to the snapping and popping of it, smelled the scent of wood smoke. Dad would take another drag off the Winston and then launch into one or another of his stories.

In one of his tales, he recalled high school at Morrow. Among his buddies there, he joined with three friends in a quartet that performed on the Fayetteville radio station. They were late one day, racing down the road in a Model T. As they approached the railroad crossing between Cane Hill and Prairie Grove, the freight train whistle sounded loud and long. In those days, the trains were endless. The quarter didn’t have time to wait. So the driver floored that old car, and they barreled through the turn on two left wheels and a cloud of dust seconds before the steam engines roared across the road, whistles blaring and the engineer shaking his fist at them.

He’d have to stop and laugh about that, full of renewed vigor.

On occasion, my dad would muse over his adventures teaching singing school. The shaped note method simplified the more arcane aspects of reading music, and folks would flock to these gatherings, although the popularity had as much to do with socializing as it did with music. He liked to reminisce about the time he forded the White River at Goshen to teach singing school there. Mid-river, he fell off the mule and wore wet clothes the rest of the day.

His father’s job with the railroad gave way to the Depression, and after trying to make his way with blacksmithing, in 1933 the family moved to West Memphis. Dad was in his last year of high school, so he stayed at Morrow in an arrangement with the folks who owned the general store. He would live at the store and keep the fire going in the wood stove overnight so the canned goods didn’t freeze. After a few months, he got word his mother was sick, and he had to hitchhike to West Memphis. He had nothing but an apple in his pocket.

When he told his stories, Dad didn’t have to look at Cotton to know he was paying attention. Cotton came from the same times.

The flames would leap high in the air, twice as high as the shimmering cone of wood, twisting into the air like a curling orange hand with only a faint grey vapor of smoke rushing from the top of it. Periodically Dad or Cotton would walk around to the side or back of the pile and pick up ends of logs or still-burning sticks that had fallen out of the path of the flame and throw them back onto the fire. Each thrown piece caused a great cavalcade of sparks to explode into the air, a celebration of new fuel, of longer life to the fire.

Cotton would stay with my dad while the fire burned down, sometimes for the rest of the afternoon, poking at it, throwing on newly discovered fallen twigs or dead weeds to keep it alive. By that time, there was little talking. Dad would use the shovel to drag the last few little unburned pieces over to the center of the ash circle where the coals ate them up in quick yellow blazes.

Finally Cotton’s wife would call him home to dinner. Mom could have called Dad too, but he wouldn’t have come. He would lean on the shovel, watching the red embers swell and throb in the slight breeze of dusk, until the last bit of fire had died.

My friend’s grandmother probably labored slowly, moving from place to place in her yard to collect the fallen twigs, carrying the brown paper grocery bag in her stiffened hand. Breezes would have lifted the tendrils of white hair that had escaped her tidy braid, and she would have stopped on occasion to stare off in memory of past times, when young she might have run laughing through green spring fields chased by a lover, perhaps examined in close intensity the phosphorescent emerald glow of new moss at the base of a big tree. Each time she bent to a fallen twig, a fresh scene spilled into her mind and she was transported to a better time. Later, she may have sat on her porch to review the tidied yard and the merits of her life.

That hasn’t happened to me yet but I expect it. For now, gathering fallen twigs is a practical exercise when I have come outside to put scraps in the compost or rake a few more leaves. But gathering twigs and preparing for fire leads me to examine the purpose of my existence. In the long tradition of humans and fire, I seek proper reverence for the knowledge I carry forward, the experience of my father, of all the grandmothers, who depended on fire for survival. We are removed from that now. My children in their comfortable homes have no need to build fire.

Yet there is ceremony in every fire. When I begin to clear a brush pile or dispose of too many fallen leaves, I think of composition, how the tiny start of flame will need room and air to burn upward, where larger limbs should be placed to catch early and burn long. After all the fires of my life, each new one is still an experiment testing whether I can prove my worth.

The flames of my success warm me and encourage me. My success is the fire. Its flames live on my arrangement of wood and air, orange and red, leaping and cracking. Embers fall to the ground and glow in the gathering bed of hot ash. My thoughts and life rush outwards in a vision of times more than my own, more than my father’s.

The ancient tribe has gathered and their shadows circle my fire.